OUR RISE AND HIS FALL

In 1974 upon leaving the group Maxayn, I was determined not to play in any more bands. The experience had given me the foundation, knowledge, and skills to form my own production company. I wanted to work as an independent producer, writer, and session musician. It was time to focus on my own ideas independent of other egos and opinions. During my time with Maxayn, I had established relationships with artists including Patti LaBelle, Charles Wright, Betty Everett, D.J. Rodgers, Franky Lee, Cix Bits Blues Band, Actor “Glynn Turman”, GT’s Back Yard Blues Band, and the late Johnny “Guitar” Watson, as well as other up, and, coming acts. It was “Guitar” Watson, however who really caught my attention. I began working with him on a full time basic in 1975, we saw each other almost everyday, and often spent forty eight hours or longer in each other’s company.

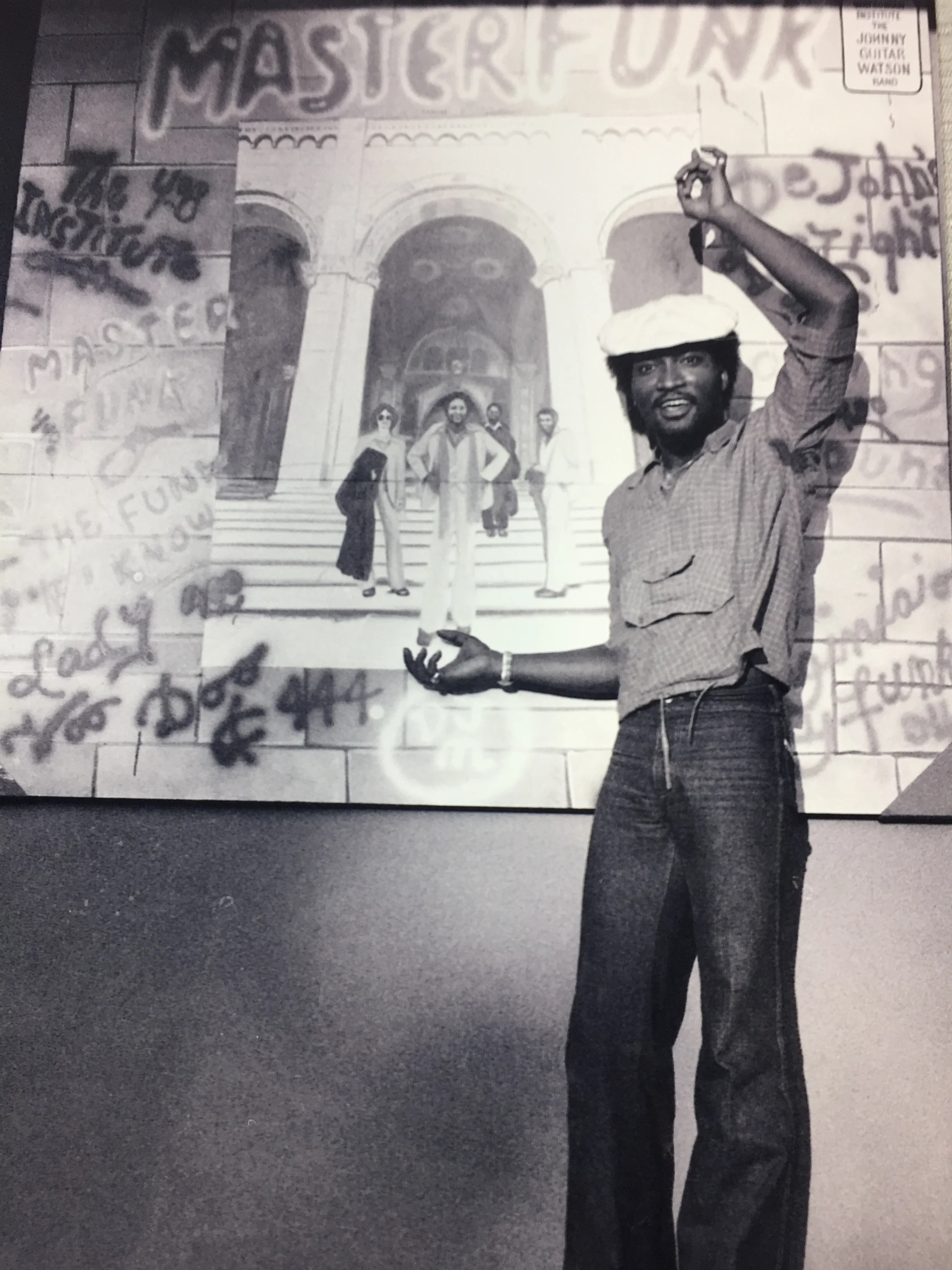

E.T. AT RECORD SHOP SELLING THE INSTITUTE

“GUITAR” ON TOUR IN EUROPE

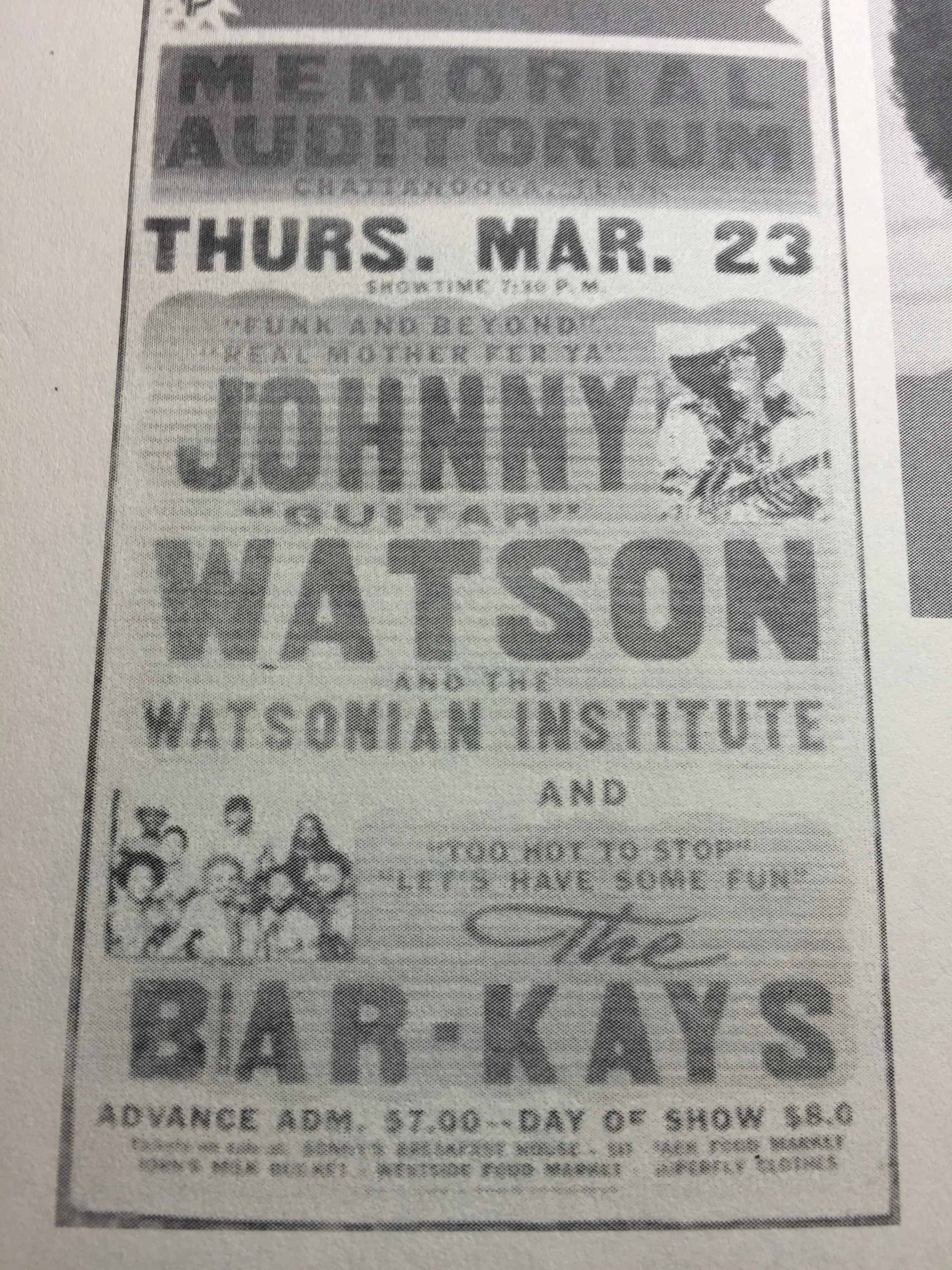

MY BAND THE WATSONIAN GOT BILLING ALSO

Watson became my mentor, my big brother, the one who introduced me to the ins and outs of the Hollywood night life. When he and I initially started working together, he had been out of the business for a while and had changed his image from that of a Blues/R&B artist to a Funkster. Through out his career Watson often reinvented himself. In the fifties when I was growing up in the Houston area, he was one of the young blues musicians hanging with future blues greats like Lightnin’ Hopkins, T-Bone Walker, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Albert Collin and Johnny Clyde Copeland. These were the guys young musicians on the Gulf Coast admired and who made up the Houston blues scene. When Johnny Watson left the Houston area for Los Angeles in 1950 at age fifteen, I was only a year old. His primary instrument at that time was piano, which he played on “Motorhead Baby” by Chuck Higgins. Watson also sang lead vocal on the track for Combo records in 1952. I remember in 1976 Watson introducing me to Chuck and telling me how Chuck had started his career. He was listed as “Young John Watson” when he signed with Federal records in 1953. Watson moved to the Bihari Brother’s RPM label in 1955 and recorded tracks including “Hot Little Mama”, “Too Tried”, “Someone Cares for Me”, and his blues classic “Three Hours Past Midnight”.

He got his first hit in 1955 with a cover of Earl King’s “Those Lonely, Lonely, Nights, and in 1957 when I was seven years old, he recorded his classic “The Gangster of Love” on Keen records. Watson would again record “Gangster” in the early sixties for Johnny Otis’s King records. ( I was later given the opportunity to re-record the “Gangster of Love” with Watson in the 70’s for DJM ). In 1962 Watson recorded another of his classics “Cuttin In”, and in 1964 he recorded a Jazz album playing piano for Chess records. In 1965 when I was fifteen and just starting my professional music career, Watson was touring with his longtime friend Larry Williams. The Duo recorded several singles and an LP for Okeh records called Two For the Price of One; among their successes was the first vocal hit on the Jazz track “Mercy, mercy, mercy, by “Cannonball” Adderley. I later hung out in the mid 70’s with L.W. and “Guitar”, and at that time I remember seeing more cocaine than I had ever seen in my life.

In the mid-70’s, Watson suggested that since I had been producing and playing drums on all of his recordings, I should work exclusively with him. I informed him that I was not looking to be in any more groups. I explained I wanted to focus totally on expressing myself as a producer and writer. When Watson realized I was not interested in being in a group, he countered with “ What if it was your group E.T.?” At this point I realized I could have the best of both worlds; production assistant/Co-producer at Vir-Jon and the leader of my own group. Once we agreed on me being in charge of the group, we decided upon a name. Watson wanted to call my group a “Thousand Watts,” to which I said no! I decided the group would be called the “Watsonian Institute,” indicating the study of Watson’s music. Andre Lewis and I had always approached Watson’s music as a study of the blues and Watson was a master teacher.

At first Watson, Andre, Rudy Copeland, and I worked club gigs on the West Coast. We started at places like Ruthie Inn, a blues joint in Oakland which would shake and squeak when the dancers took to the floor. We grew to eventually performing in venues including Carnegie Hall in New York City, and Hammersmith Odeon in London. In the beginning we toured in a mobile home filled with equipment and six musicians; Watson would always fly. With the success of “Ain’t That a Bitch,” and “The Real Mother for Ya,” Watson purchased a double-decker Grayhound bus. We toured all of the major markets in the U.S.A., and endured the many hardships of being on the road, the breakdowns, the snowstorms, and accidents. I persevered because I wanted Vir-Jon, Watson’s company to succeed. When funding failed to meet our expectations, I continued to focus on the big picture. Vir-Jon was set to become a major player on the West Coast music scene. Vir-Jon had produced the Watsonian Institute, Randy Redman, Johnathan “Flash” Wilson, Franky Lee, Betty Everett, and the star act Johnny “Guitar” Watson.

From Watson’s humble beginning to his hit record successes, I was there. From Watson rolling a joint using a brown paper bag because he had no cigarette papers, I was there. I watched as he destroyed himself with ounces and ounces of powered destruction. I put in all those years with Watson in hope of establishing his label Vir-Jon. I believed we had the same vision for his company; I was wrong. When Watson failed to get the support he felt he deserved from Dick James, his whole attitude changed. Drugs, mismanagement, and bad advice further contributed to changes in his personality. As a production team we had great chemistry, and, because we controlled production, we were able to do things that defined who we were. Watson’s guitar sound and my drum sound were our trademarks. While DJM initially provided adequate resources, Watson expected a lot more after two gold albums. When it failed to materialize, he no longer wanted to be affiliated with DJM.

In the mid-70’s Watson’s focus had been laser sharp. He dotted all the I’s and crossed all the T’s. It was great to be with “Guitar” back then; the music was paramount. We played music from the 50’s and 60’s, tracks like “Cuttin In” and “Gangster of Love”. We had a hit with what was also my first hit recording “I Don’t Want to Be a Lone Stranger” for Fantasy Records. This was also the beginning of our run at DJM, with hits like “Ain’t that a Bitch” and “The Real Mother For Ya.”

It was while touring with groups like the O’jays, the Commodores, and the Whispers, that Watson and I spoke of what it must be like to have a catalog of hit recordings. To be able to play hit after hit after hit. The irony for me was, that when we finally achieved that goal, I was no longer a part of Watson’s organization. As a young musician just starting out in my hometown of Galveston, Texas, I had had the opportunity to work with legendary soul singer Etta James. While still in high school I played a full Stax-Volt Revue featuring Arthur Conley of “ Sweet Soul Music” fame. Later while attending North Texas State University and working the Dallas club scene I played with Jazz saxophonist the late Hank Crawford. These events formed part of my rise to the status of professional musician. I had also worked the chittlin circuit as a young musician in places like Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Louisiana, Colorado, Missouri, and Halifax, Canada. Upon becoming a member of the group Maxayn, I attained international stature, working in Italy, Portugal, and France.

Working with the late Johnny ”Guitar” Watson should have led to the high point of my musical career, but our time together ended with Watson going to A&M records on his own. DJM had opened the door for him with two gold albums. Watson was given the chance of a lifetime, to sign with an elite label like A&M records. However, A&M rejected everything he submitted on his own. Prior to his death Watson spoke to me about how he had missed the opportunity with A&M. He apologized for what he had done to Vir-Jon and to me. He shared his thoughts and took total responsibility for what he had done. This did not really hit me until much later. When I found out that Watson had been given a multimillion dollar deal that did not include me, I was very disappointed. As fate would have it, A&M rejected everything he submitted.

Watson and I produced great music for DJM. Productions that doubtless led to the offer from A&M. DJM had gotten him gold records, with the right material A&M should have been able to get him platinum. What Watson did at A&M on his own was an embarrassment. Everything we had achieved for Vir-Jon was lost because of his ego. I know now without a doubt that my input had been essential to the success of Watson’s projects. Blinded by drug abuse and bad advice, however he turned his back on me. At first I questioned what had happened, then I realized Watson was deliberate in what he had done. He consciously and intentionally destroyed everything we had created for Vir-Jon in order to promote himself. Watson was given a million-dollar deal on the basis of what we had achieved as a team. By failing to include me in his A&M deal Watson blew it. It turned out that he could not fulfill his commitment. He was not able to re-create on his own what we had done together for DJM. In destroying this opportunity Watson lost millions of dollars. A standard record deal is usually three years with a two year option. Watson could not take advantage of this gift. He should have gotten at least three years out of the deal, but he barely got one. There is no doubt in my mind that our musical chemistry mattered; Watson disrespected that reality. As it happened Watson was dropped from the A&M label and black-balled from the music business through out the 80’s.

He returned to the business in the early 90’s with recordings like “Strike on Computers” for Bell records. He also had a track called “Bow Wow”, which did make the charts. In one of his last interviews Watson indicated that no label was interested in signing him.He related that this drove him to establish his own label and that he had finally gotten control of his musical catalog with all revenue coming directly to him. He was very happy about this and was looking forward to the coming year. I was left to wonder why did he not see this in 1978 when we tried to get him to go independent. Vir-Jon and everything we did for Vir-Jon should have been underwritten by A&M records. Johnny Watson missed the great opportunity to be like his boss Herb Alpert, the “A” in A&M records. We were given the chance of a lifetime and Watson threw it away. Johnny “Guitar” Watson was in a great position to do unprecedented things for the people who supported him, and he chose not to. I have accepted that I will never be paid the thousands of dollars owed to me by Vir-Jon, but the life experiences I gained from that period are priceless.